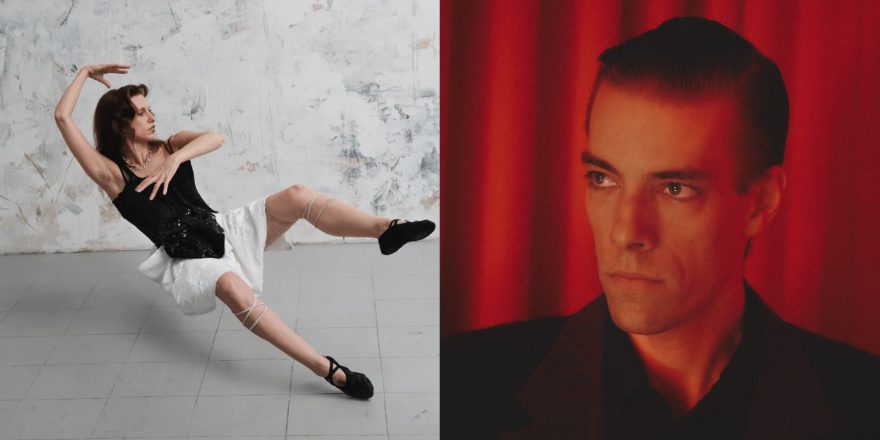

Carson McHone is a singer-songwriter and multidisciplinary artist from Austin, TX, now based in Welland, Ontario; Allie Blumas is a dancer, musician, and death doula based in Hamilton, Ontario; Deanna Jones is theater director, actor, and writer who runs Suitcase in Point, a multi-arts organization in St. Catharines, Ontario. Carson’s forthcoming record Pentimento will be out September 12 via Merge. Ahead of the release, she’s partnered with Allie and Deanna to develop a performance project in three acts based on the album, incorporating light, shadow, and dance. One piece of this collaboration is the new video for Carson’s track “Idiom,” which was co-directed with Allie and Deanna. Check it out below, and read their roundtable discussion about its creation.

— Annie Fell, Editor-in-chief, Talkhouse Music

Carson McHone: OK, we were talking about Richard Brautigan. Do you remember the title of the piece? I can’t remember it — something “YMCA”…

Deanna Jones: Yeah, “Homage to the San Francisco YMCA.”

Carson: Exactly. It’s hilarious. It’s about replacing your plumbing with poetry. But before that, Allie was talking about using decomposing bodies as power, because decomposition is energy.

Allie Blumas: And if it ever comes to fruition, we can be like, “You heard it here first.”

Carson: And that’s where the big bucks come in. Because that’s all we care about: raking in the dough. [Laughs.]

The three of us have been meeting almost weekly for months now. I mean, with bits and pieces on and off — we’ve all been off on tours, or out of town and doing our own musical projects, or whatever — but pretty regularly. And I find often that the three of us get in a room together and end up having a great conversation. But I was thinking about how we’re actually having this convo on the record now, and I was like, Oh, god, what are we going to talk about? I texted my mother — who, her voice is heard on the album — there’s a quote that opens and closes the record, kind of, and hers is the closing quote, in response to this Ralph Waldo Emerson thing that’s said at the top. But I told her we were doing this, and I was like, “What do you think we should talk about?” And she said this beautiful thing: “What about the importance of metaphor and play in fraught times?” I was like, “Uh, yeah, that’ll work.”

Deanna: Woah, mom!

Carson: Of course she would say something like that. But also, that’s what we end up talking about. We’re talking about the fraught times that, every step you take, you’re affecting the world in some way. And this moment especially, it’s becoming very, very clear to us the steps that we take that have negative ripples. How we spend our money, how we ask people to engage with our art — you know, there’s monetary ties to everything, and we don’t have direct control over where those things go. And then we’re talking about energy, and of course metaphor and poetry come into play. And that’s why I brought up Brautigan, because it was this hilarious metaphor of replacing plumbing with poetry, and how it doesn’t work really, but it’s very funny. And then using your own bodily fluids to sustain battery… It’s all these creative things that manifest to solve the problems that we have. And that’s what both of you are doing all the time, whether it’s through theater and comedy, or writing and playing music, or moving your body and understanding that the written word or even how we communicate is so fickle. And that we use these metaphors — whether it’s literally with language or if it’s with our bodies or sound — to communicate and solve problems, and process things that having a normal, straightforward conversation [can’t]. And that, in what we’re doing, play and creativity is how we imagine a better world.

Deanna: It’s funny, too, the metaphors — I was just thinking about titling some of the stuff that we’ve been [working on] in improvisations. What it feels like or looks like becomes a tangible thing that we can reference. Now I’m thinking of another project, but there’s a thing [we call] “fish sticks.” It’ll be like, “Oh, we’ll go back to fish sticks.” And it’s like, What the heck are we…? [Laughs.]

Carson: Right, if someone were to pop in they’d be like, “What?”

Allie: Yeah, definitely can relate to that. I said this from the very beginning, but the first time we all met and set up the scrim and really started working with the lights, I was like, “It just feels so good to play and experiment in this way.” It’s so important because it’s this multi-sensory experience where you’re engaging all of your senses, but then your childlike self is also being activated and remembered and honored in this way. And then you’re also problem solving — you’re just trying to come up with creative solutions for things. But I think it also helps us find meaning, not just in the actual art work that we’re trying to create, but in our own individual selves as well, and what creativity means in our own lives. I feel like that’s so important because in death, we talk about finding meaning after someone has passed away and how important that is, but we don’t often talk about how important it is to also find meaning in life. I feel like that’s what everyone is trying to search for, but we don’t explicitly name it or call it that. And I feel like within this process of play and improvisation and experimentation, it is meaningful, and it’s also finding meaning and understanding the purpose.

Carson: Yeah. I guess for me, bringing this project as an album to the two of you, was a really methodical thing. It was like a gathering of meaning and then assigning that meaning into spoken word or song or whatever, and it’s been collaged into this album that’s this contained piece. Bringing my mom up, for example — having access to this journal that she kept when I was an infant — I’m gathering these artifacts. I have these poems that were written on envelopes, sent through the mail. [I was collecting] many different things, and then structuring them all on a page. I had no idea how to assign instruments or how we were going to play things necessarily, but all of that work to prepare allowed me to be like, “OK, we put this stuff on the wall around us, now we play.” Then the results of that are the album. And it continues out now and involves the two of you, and there’s movement and light and assigning names to things. We’re being methodical about certain things. And there’s meaning there — my own meaning — but it’s expressed musically through this album. So then it’s a matter of bringing this forward and then stepping back, because we don’t need to pin down the meaning. It’s now wild in the room with us, and however that manifests in the two of you is once-removed in a way. Except for that it’s not even removed. It’s just an extension of it now.

Allie: There’s the record, which has its own meaning, and then it’s finding another meaning within it.

Carson: Well, it’s its own meaning to me. But I remember one of the first meetings that we had, we listened to the record together and took notes, and it was so much fun to hear y’all talk about the songs. One of you said, “Carson, what’s it like to just sit here and have us tell you what your songs are about?” And it’s really funny because one of the first conversations I did for Talkhouse was between myself and two other members of a band I’m a part of, and I think they titled it, “We Want You to Tell Us What Our Songs Are About” — which is really funny. But we’re offering up our own meaning and then watching it grow wings or legs or whatever.

Allie: Yeah, people find their own meanings and interpretations within a meaning of someone else’s.

Deanna: That’s what’s so fun, too. I love how you said it’s “wild in the room,” because everybody brings their own interpretations, their own memories, their own experiences to things that they experience. And what’s so nice about this is that you’ve opened up your process and it’s a highly collaborative thing. You can feel that when you’re listening to the music, that sense of that special thing that happened in that place. Not only in the room, but the birds outside — all of that energy — and the artifacts. I feel and sense that. It’s just so rich.

It’s neat thinking about death and grief, too, because sometimes it feels like when a show’s up and ready, or maybe when the album is cut and it’s in someone’s [hands], it’s almost like there’s a grieving of that. The process is now over and it’s out there. But what I think is so special is there’s so much emphasis on the process.

Carson: When I’ve spoken to people about this project — specifically about this performance project that we’re developing — I always talk about it with the caveat of, “Yeah, we have this really grand idea of involving these seven musicians and multiple dancers and all this stuff, and it’s sort of reliant on whether or not we are able to find funding.” But also I was like, “I’m so lucky that both Deanna and Allie have committed to doing just this one portion of it in September with the album release no matter what.” And honestly, even if that didn’t happen, it doesn’t matter. It’s been so incredible just to have this as an exercise. That’s so meaningful to me.

Allie: I was literally just thinking about that. I think for me, process is the whole thing. That’s why I make art.

Carson: I’m obsessed it.

Allie: Yeah! It’s always been a big part of me, and it’s how I’ve always created work with the other dancers that I work with. It’s so much about the process to the point where we never fully choreograph things — we go in there, we have a show to do, and it’s all just a structured improv. I know there are these moments that work because we played around so many times, but even the end result is still a process.

Carson: Oh, yeah.

Allie: This is why this has been so meaningful, because it’s all about the process, and it’s all about play and discovery and failure being a teacher. Not like there’s been any real failure in this process at all. But, yeah, I was just thinking that if I never finish a piece of art ever again, I think I’m OK with that. Like, if I’m just always in process with something that’s really meaningful and helping me discover more about myself and the world around me, and connecting to other people, that is so cool. And if I never finish anything, I think I’m OK with that.

Deanna: It’s funny to think of, “Oh, if we get the funding, it’ll become this” — we were watching some of the video of that full improvisation of the whole album, and I don’t know that I’d ever expected that we’d be, like, puppeteering lights. We [had] these lofty ideas of multiple dancers and this incredible lighting designer and “we’ll have all the cues set” — and then through the process, in my mind I’m like, This DIY-ness is so unique. It’s so unlike anything I’ve ever seen. I don’t know how tangible it is to repeat and repeat, but it’s so exciting. And it’s a discovery you make just because you’re screwing around and playing. It’s like that available light theory — we already have enough.

Allie: Yeah. Sometimes the limitations are exactly what you need.

Carson: Totally. And they’re exposed — the tactile nature of all of it is exposed to people. I think sometimes you can see or hear something that you don’t understand, that you’re like, “Oh, my god, I gotta figure out what that’s like.” Then sometimes experiencing something like that is like, “That feels so out of reach, there’s no way.” And I think I’m super excited about the DIY nature of this stuff, just because it feels like it could be a catalyst for people doing things with limitations, in whatever scenario. You can see the moving parts, and it’s like, “I can do that, too.”

And if it never sees a larger audience, we’ve still been in conversation with these ideas and with each other, and I think that is the point of art and love. I remember when I was trying to think about these songs and poems that I was putting together for this record, I was talking to Daniel — my partner — and my mom, and we were talking about art and, “Is it art if you do something and then nobody ever hears it or sees it?” It’s funny because how you define “nobody ever seeing it” or “nobody ever experiencing it” is where that distinction lies. Because if you’re in conversation with something or you’re in communion with something greater than yourself, that’s already being shared.

Allie: For sure.

Carson: I think that’s kind of inherent in engaging with the creative parts of your mind. You’re engaging with something that is already bigger than yourself.

Deanna: It is such a blessing, whether or not anybody sees what we’ve done — which, they will — but I work in a place where having an audience is so integral to it, to the end part, and it’s not very often that as an artist, I just get to be in a room and be inspired and just feed myself and each other in creative ways. I know that there’s an end goal in sight, that there’s something that we’re trying to do, but that serves me whether or not this was a tangible thing that at the end had an audience-performer relationship.

Carson: That’s so important to remember. Right now, I feel like we’re all paying a lot of attention to the negative effects of moving through the world. And at the same time, it is true that the good conversations and the creative webs that we’re spinning are also out there continuing and being picked up by who knows. You carry yourself in a different way, you approach things differently, when you are allowing yourself to be playful and think creatively. And I think those things are going to be more and more necessary in the times that we’re living in. So to be exercising those things already, I think, is crucial. I’m encouraged by it because I feel like in situations where we will feel forced to change how we do things, it’s going to feel less like we are reacting or we’re being forced into a different way, and instead it’s going to be like, we’ve already begun laying this path or thinking in these ways.

Deanna: I always grapple with this idea of art as resistance. I understand it, but it also feels like being in this world as my profession — it’s just something I feel like I can’t get away from. But then it’s like, Who cares about this? This isn’t affecting anything. And having conversations with other artists… not everyone spends time justifying what they’re doing all day long, but it just feels like, OK, you know what? If one person in the world one day hears your music or sees this thing or is affected… I don’t know, I still grapple with it. I also get that, despite how shit the world is, the sense of community or shared experiences or people having culture helps, because without it we’d be totally fucked. So we need water and urine batteries, and we need the show that we’re working on. [Laughs.]

Allie: I talk to my sister about this all the time, about art being an act of resistance, whatever your medium is. On one hand, you’re like, Well, I don’t want to think too highly of art or the things I’m doing. But I think the crucial thing is that whether you decide to make art and show it to the world or you decide to just make art for yourself and never show anyone, ever, it’s the same in the end because you’ve decided to do something.

Carson: It’s the process. It’s an act.

Allie: That’s different than what a lot of other people are doing, and that is an act in itself of defiance. Creating art is going against the status quo, so to speak. It’s a powerful form of resistance. And within making the art — again, regardless of who it’s for — it’s connecting you deeper to yourself.

Carson: And to humanity.

Allie: And to humanity. You’re being rooted more in this way, and we all know how being rooted and grounded is so essential in these really intense, fraught times of upheaval and people vibrating at these other levels because things are just spiraling out of control. We need something to ground ourselves and connect us back to ourselves, back to our community, and again to find meaning in what we’re doing. And art continuously does that, always. It’s like this existential cycle of being like, Oh, my god, what is this for? I should just quit. And then you get back to the root, This is why I do it.

Carson: I brought up that conversation about, “Is it art if…?” And I think I was thinking about it in one way instead of another, and it made me have this weird, funny angle on it. I was considering justifying your art, or justifying the pursuit of that, and then I was thinking, Well, the point of all of it is process and connection and being connected. And then I was like, It’s the same as love. But we’re not all sitting around like, “Oh, yeah, you’re in love? Justify it. Is that really worth your time?” But it’s the same thing.

Allie: Yeah, totally.

Carson: You’re figuring out about yourself, you’re figuring out about others, and you’re bringing your experience — because you can only bring your experience — and then you’re like, Other people are gonna look and be shaped in similar ways, but they’re gonna see it from a totally different perspective, and we’ll never be able to see it exactly the same. And yet, it’s like, Wow, we’re connected! It’s so magical and so wild, and there’s no justifying it because you don’t have to.

Deanna: I love that. But it’s funny because so often — [in Canada], anyway — you have to justify it. You’re constantly writing grants or justifying how your art is contributing to economic development or to society or to try to put a value to try to keep the cash. It’s a labor of love, but then it’s also that sense of, OK, I’m trying to do a fundraiser for this project. It’s super important that I get the cash. When, like, I look out the window and there’s 16 people on the street who need money for food. That’s where I get into this thing.

Allie: For sure.

Carson: Well, one of the things that I keep coming back to — because I am having to put language to this piece of art that I made that then became a collective thing — I have to define it and nail it to a wall and work to put it out into the world — but one of the main ideas that I keep coming back to, and why we are playing with light and dark and shadow and past self and future self and multiple selves, is that both things can be true at the same time. There are many, many layers to all of it. There’s multiple truths at the same time.