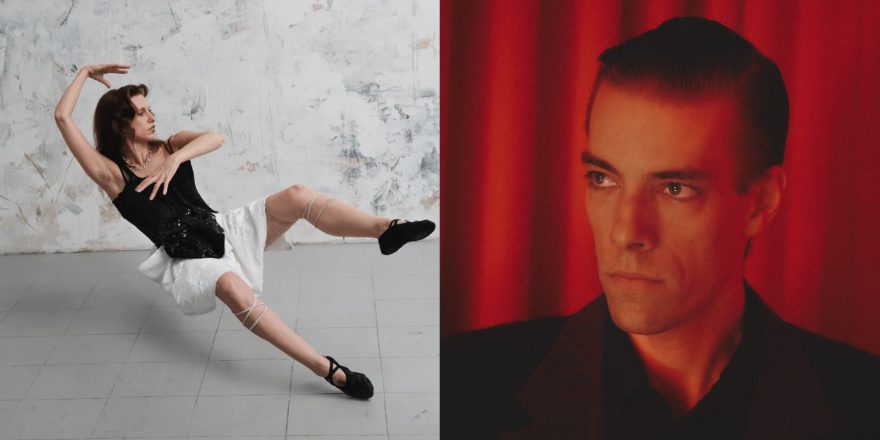

Xol Meissner is Mauro Hertig, a Swiss-born, classical composer based in NYC; Glasser is Cameron Mesirow, a singer-songwriter and producer also based in NYC, whose latest record crux came out in 2023. The debut Xol Meissner record, Excess of Loss, just came out last month, so to celebrate, the two artists got together to catch up about it.

— Annie Fell, Editor-in-chief, Talkhouse Music

Xol Meissner: I’m really excited to get to some of the guts of the music that you do. I listened back to your albums and one thing that really struck me, especially on the last one [crux], was the digestive aspect of desire and of love. In the lyrics, there’s often talk of eating and swallowing, and this idea that the object of desire can become part of your body. I thought that was super interesting. And then once I thought of it, it kind of started popping up in all tracks.

Glasser: Oh, my god. I don’t think I’m aware of that.

Xol: Oh, wow.

Glasser: I think consumption is a really big part of all things I’m passionate about. I luxuriate in consuming. I didn’t, for instance, actually make anything in music for a very long time, until 20 years into consuming like crazy. I was already such a music junkie by the time I was 15 or something, but I didn’t really even start making songs until about seven or eight years later from that. It’s like I was just full up on having consumed. I had ingested and ingested and ingested. And I think that is also maybe a bit how I am with love and affection — I really go all in, or I don’t go at all. I want to just lose myself completely in a person and I want to possess them. [Laughs.]

Xol: I think it definitely shows in the music, in the most beautiful way.

Glasser: I feel so seen — or caught!

Xol: [Laughs.] But that’s interesting, also, this aspect that the consumption of music, as you say, early in your life was also like a love affair.

Glasser: Yeah, absolutely. Total fantasy. I’m like that with food as well.

Xol: Oh, with real food?

Glasser: Yeah, food and wine, and just all things to indulge in. Not TV — I mean, there’s some of that too. But it’s more like sensual pleasures. I lose myself in a fantasy of trying to taste everything about the food or the wine or whatever.

Xol: Is it also connected to other senses? One that sometimes popped up, I feel like, was the sense of smell.

Glasser: I think so. I, after being such a crazy music person for so long, I discovered my love of olfactory pleasures. I mean, perfume is a really big thing right now and I am really into perfume, but I’m also just into other types of scent. I think scent is one of the most bountiful fantasy playgrounds. [Laughs.]

Xol: Hell yeah. And I love the transition from how you came to music to then how you came to actually write music. There’s a parallel in there.

Glasser: Yeah. What about you? From what I know, there’s a structure to your lyrics — you’re concerned with structure. There’s references to relationships, power structures, parental structures. I’m thinking also of the poem that you read to me when I was in your studio, that was all about a community structure. At least, this is my pattern recognition happening…

Xol: Yeah. I mean, to be fair, I think sometimes food pops in as well, or consumption, but in in a different way. It’s more sometimes in a disgusting way. It’s not always in a sense of desire or all-consuming love, but sometimes in the context of decadence.

Glasser: Gluttony.

Xol: Yeah, or when something is too much and you ingest something but it doesn’t belong. So it’s a much less a nice way of including consumption in lyrics. [Laughs.]

Glasser: But it’s so valid at the same time. Like, there is a point at which we’re too fed. Too many pleasures don’t really amount to more pleasure.

Xol: But you mentioned structure, and it’s true that I often have these structures as a base, but as an almost banal kind of base. And then I try to play with it, break it with objects or narrations that don’t necessarily belong in this structure. In this track “Breeder,” which is the second track of my album, it’s a kind of a process of being brought up, of being raised basically, but it’s in a constant transformation. It starts as a flower that is raised, that is cut off in bloom, made to look pretty. Then the second verse is about a cocoon, something inside of this protective shell that is then about to transform. Later there’s talk of birds, of the seed that is going through the digestive tract of a flying bird that then is shat out and grows again as a plant. I love these up and down movements and digestive processes, to impose them upon such a simple structure like a baby and a parent.

Glasser: That’s beautiful. It sounds very much about a struggle to let go of control, or something.

Xol: Yeah, totally. Structure is something you hold on to. But then you might realize that actually, the structure itself is potentially rotten. But you only realize after the structures are already falling, and then you have to learn how to fly and land softly. But then you realize the floor is actually super muddy, and so on… I love these kind of processes that are triggered.

I felt there are like a lot of parallels in our lyrics, but the way it sounds is very different. I really enjoyed when I listened to your music this kind of mix of the machine and the heavy with your incredible voice that floats and finds spaces between. It works extremely well. And this contrast that they’re hyper percussive — but that was more on your earlier albums.

Glasser: The new one that I’m working on is extremely percussive.

Xol: Exciting. What kind of percussion do you use?

Glasser: I really like industrial sounds — I like a sort of machine-like drums sound. But I also like to use organic things and make them sound like a machine. And it is just by nature what is happening because I’m using VSTs and I’m working in Ableton. But as a vocalist, I think I have a lyrical approach to writing percussion.

Xol: Oh, that’s interesting. Can you describe that, what that implies?

Glasser: I really like making fills, and when I listen to music I’m quite focused on the rhythm section… I would have to play something for you to show you what I mean, but I do really think of the drums as a voice in the scenario.

Xol: Would you have them looped and then already try voice along with it while programming the drums?

Glasser: Yeah. I thought it would be cool to do a whole album of just drums and voice, actually.

Xol: Yes! That’d be sick.

Glasser: I haven’t ever succeeded in that because I also really love lush pads and things like that.

Xol: I’ve heard, yeah.

Glasser: I was really into using lots of violin and flute and stuff like that, but right now I’m really focused on rhythm. I really want to dance, and I’m concerning myself with warm weather. I mean, it’s warm weather right now, but I’ve had this comment several times in my career, “You make cold weather music.” And so I’m trying to make warm weather music. Because, also, I was only invited to play in cold weather places and I want to go where it’s warm. [Laughs.]

Xol: That’s so interesting. If you’ve been accused of making cold weather music, I’ve been accused of making music from a different time.

Glasser: Well, I can see that. But I would say more timeless.

Xol: Oh, well, that’s the nice version of it. The sugarcoated version of it.

Glasser: I mean, ultimately these things are compliments, right? They’re some kind of feedback. But I also think that we know, as those in the position of making the stuff, what it feels like to be ourselves and what it feels like to respond to a calling to make something — that isn’t necessarily borne of a shared ambition with another artist. It’s just this magic that occurs and you’re like, Wow, I want to be in this magic. I want to be here with this. That’s how I feel, anyway. My body is very tuned in some way to catching these melodies out of the air.

Xol: This moment you talked about when you feel like a melody is yours, or when you share this moment with the melody — it’s really with this project that I have felt this kind of fire. And the way to get there was a bit complicated, because I used this weird guitar technique that you’ve seen at the concert, where it’s played lap steel style with two metal slides. I’ve used that technique for other guitarists, [when] I wrote scores for other guitarists, and I was never fully happy with how they did it.

Glasser: Which is probably why you had to do it yourself.

Xol: Yeah, then I started doing it myself. And it came at a similar time where I wrote more and more text, and I didn’t know how to use this text in a classical context. I didn’t want to write opera style, for people with this incredible vibrato. I really felt like there was a way to combine it. And then inverting the roles — because usually what you would do, probably, when you write songs, is you’d have a piano and then put the voice above. And in this case, because this guitar technique is so fragile and high up in pitch, I put the voice below. When I realized I could do that, and I had the first couple of phrases where I found melodies and then I combined it with the harmonies from this experimental technique, I was like, Wow, this should be my life now forever. [Laughs.] It was so beautiful, and it hasn’t stopped and I’m so happy. I feel like it’s the kind of pleasure which, as a musician, maybe only a song can make — this intimate connection that then hopefully transpires to an audience. But this moment, the first contact with a melody that is really tailored to your own voice, I feel like it’s a very special thing to happen.

Glasser: Maybe there was something about it, too, that was a uniquely precise way of sharing yourself. Because I think that’s what songs do — they bridge us. They’re a more direct communication with the listener, or someone else singing along with you.

Xol: Do you think by writing songs, you change future experiences of yourself as well?

Glasser: Ooh… It would be nice to write with that in mind. Can you say what that means to you a little bit?

Xol: Taking the example of your songs, I love this track from crux, “Easy.” That’s probably my favorite track at the moment.

Glasser: Oh, really? That’s so funny. I would never have guessed that was your favorite one.

Xol: Really? Why not?

Glasser: I don’t know. It’s the most poppy.

Xol: It’s so catchy.

Glasser: It’s so poppy that I actually struggle with it. My conscious listening brain, as opposed to my unconscious listening brain, refutes the poppiness of that track always. I had a really hard time finishing it and deciding to go with it. There were lots of people who liked it and were like, “Let’s go, this is a great track,” but I truly did have a hard time attaching myself to it.

Xol: I understand. I mean, to be fair, I have a list of tracks, but this one is the one that, probably because it’s so catchy, [is my favorite]. And it starts with the double melody that are very cleverly composed, but the lyrics are actually quite intense, which I love. You also have this decelerating in the beat.

Glasser: That’s a lyrical percussive move!

Xol: It works so well. And the way it goes back into the regular beat, it’s pristine. But the lyrics are very extreme. They’re lyrics of transformation — again, the digestion, the swallowing. And then by swallowing, the flowers become dust.

Glasser: It’s about someone who died.

Xol: That makes sense.

Glasser: My first love died.

Xol: Oh, I’m sorry.

Glasser: I wrote that song when I bought a plane ticket to go visit his grave site.

Xol: Woah.

Glasser: [Laughs.] Sorry it’s so intense. But it’s true. I have a before and after in my life to do with that death. That was my first experience of grief — and I walk around knowing that it won’t be my last. But it was a truly transformative experience. And I was so shocked at the very at once banal and, on the other hand, completely profound idea that his body was now in the ground. It was just so incredible to me to think of that. And that they were just all these little life cycles happening in the wake of his death. Like cut flowers.

Xol: Wow. It’s interesting that it became a song that is so catchy. Was that intended, to make it something that is very easy to digest?

Glasser: No. And I mean, “Easy” — it’s so not easy.

Xol: It’s not easy at all. In “Mass Love,” another track from crux, there is this part where the lyrics are, “The clocks were telling me to jump.” Which I thought was so wild and so beautiful. I was wondering, when you write a line like that, the next time you look at a clock do you remember your own lyrics?

Glasser: Not necessarily. That lyric is just about there being — it’s so silly, actually— there being some kind of confidence built in me. I’m a sincerely optimistic person and I look for messages of love and joy in practically everything. So my experience was just… You know, they say that we’re having the same eight thoughts every single day, and I think that when I get into some kind of pattern, especially around making a record, I get this sort of adrenaline kick every time I realize that it’s happening, I’m actually doing it. And I would have some type of thought like that and look at the clock and every day it would be the exact same time. [Laughs.] And it was somehow like a confirmation that I was given.

Xol: Wow, I love that. Like a biological, inner clock.

Glasser: Yeah, that there was some kind of tuning to it, like I am tuning to myself and this is what happens, there’s a repeated pattern that says “yes” to me.

Xol: Amazing. I want to have that.

Glasser: Well, you need a lot of time and optimism.

Xol: I have neither. I’m like the worst at those two things.

Glasser: A lot of people are really tuned to their negative thoughts, and I am here to say that you can change that. I think you just have to want to — and that’s the hardest part, actually. There is something inside of negativity that feels kind of cozy to a lot of people…

It was really interesting to listen to your record with the lyric sheet.

Xol: Does it change things?

Glasser: It doesn’t change my feeling, it just deepens my feeling. There were certain things that I had already heard several times that then stood out to me again on the page. For example, the lyric, “Spits out good taste.” I know who you are from that lyric.

Xol: Oh, that’s beautiful. That’s from “Breeder,” right?

Glasser: Yeah. There’s a full storybook in these lyrics. I feel 100% immersed and in a kind of decadent and grotesque book of fairy tales.

Xol: That makes me happy to hear that. That was the goal.

Glasser: Good, good. But I guess because I met you so soon into hearing your music, I wasn’t able to formulate as much of a relationship with your darkness — because we’d just met socially the first time that I heard you perform these songs, and you’re a nice person.

Xol: [Laughs.] Thank you. Does it disappoint you that I’m a nice person?

Glasser: [Laughs.] No, no! But I think sometimes people — and I relate to this, too — people who make music that’s at all concerned with darkness and shadow, maybe there’s some kind of expectation that in reality we’ll be dealing in these sort of poetic, proverbial types of conversations, when we’re also just regular people who, like, ride the bus or whatever. I didn’t have so much previous, let’s say, “focused” awareness on that darkness that I feel is evoked for me in a pleasant way in the music. It’s almost like a child might be frightened by the darkness that I hear in it, but I’m sort of delighted by it.

Xol: That’s very nice. Yeah, it’s definitely not music for children. The lyrics in “Breeder” about the flower — “Raised into good taste/Pull the flower/It spits out good taste/Cut from the water source/It spills in good taste/A pretty face/collected in bloom” — they were the very first lyrics I ever wrote for this project. I was in Austria at a music festival and I had three pieces of mine performed, two of which were premieres, and I was super happy. On the train from Graz to Vienna after the festival, I was expecting just to read a book or text with friends, but it really blurted out to. And it was really lyrics — it was not text, what I would usually write. It was really with a structure. Not rhymes, but a structure playing with repetition, playing with motifs. So I think without planning it at all, after that festival, I was planning the next step. Part of me was jumping right away into the next part of life.

Glasser: I love that because that also means that there was this built up energy that had to happen.

Xol: I think so. I mean, when you grow up and you choose a job, a calling, in life, it is always connected to how you’ve been brought up, how you were educated by your parents. Which I think is mainly this idea of the flower being drawn up, or pulled basically, which is a kind of forced growth. Also raised into good taste is kind of like, you learn how to behave. And then as soon as it’s the pretty face, it’s cut off and it’s used for something. Maybe it was a moment after the train where, without wanting to, it comes back to why you took a decision to, in my case, be a composer and why maybe now is the time to be something else.

Glasser: Were you a flower?

Xol: Sure. [Laughs.] I am the flower, and I’m not the flower. It’s me, but it’s also just a flower. The way people reacted to that was often that they felt like they were the flower. Which I guess most songs do that too, but I think this one in particular, it’s kind of that the person is the flower, and not it’s a flower given or something.

Glasser: I think it’s very powerful that people responded in that way, and I think it speaks to the relatable quality of that, that we are ascribed worth based on a few things but not generally the whole of us. To be appreciated only partially is still to feel unappreciated. You can still feel that there’s much more that’s being left behind in the dust.

Xol: And it’s maybe even more dramatic seen from a different angle, because you’re brought up only then to be cut off. What do you do with a cut off flower? You put it on the table and show it to guests. And I think that was a bit the topic of “Breeder” overall, this idea of very emo, very kind of neglected, “I am a flower. I am in a cocoon. I am a bird. I am a bird of its own hatch.” This is later in the song — “A bird of its own hatch/Feathers and tar as its costume/Sewn with the vigor of its makers/Trading their child for a friend.” So it’s kind of like you’ve been punished, you have this horrible costume, and it’s been made with the idea that you’re going to be traded for a friend, basically, by your own parents. So it’s like the ultimate punishment.

Glasser: I listened twice to the album, but then each time, it starts with this song “Cake.” And this song is so, like, Gatsby. It’s so totally cosmopolitan. I felt like I could feel the texture of the air in the room, I could feel the velvet of the couch, I could feel this tension in this parlor around the charade of wealth and decadence, and the kind of weird hierarchical structure of deference to that wealth. I was really swept away in that track.

Xol: Well, can I just say I’m honestly very, very touched that you took the time to listen to it two times.

Glasser: [Laughs.] I really, really felt this banquet, I felt this big announcement being made by this person who’s sort of upheld by circumstance and the situation being tense. I also felt that you were this narrator throughout the record, pointing to the different details in the room or in each story. There are some first person things, though. Is it “Pyramid,” and also “Mother”?

Xol: Yeah.

Glasser: Anyway, the funny thing about using a cousin as the sort of fulcrum of the whole event — that distant cousin, and the reference to their wealth — it immediately brings up the topic of inheritance, or a potential to share or be shared with.

Xol: The idea of the cousin — I was kind of riffing off the song “Cousins” by Vampire Weekend.

Glasser: Oh!

Xol: They were really the New York band for me when I was not in New York yet, when I was a kid in Switzerland. I loved them and I knew all the songs, and we were covering them. For me, Vampire Weekend were always a reference with the kind of fun play on decadence. And I mean, obviously, my sound is completely different. Different voice, different aesthetics. But for me, the idea of the cousin came from there, from this song.

Glasser: that’s really funny. Well, I’m sure they’d be happy to hear that.

Xol: Oh, my god, yeah. I want to meet them. I need to become just famous enough to be able to meet them.

Glasser: If this makes it into the into the piece, I know just who to send it to.

Xol: Oh, my god. When I meet Ezra Koenig, I peak. I can retire. [Laughs.]

Glasser: [Laughs.]