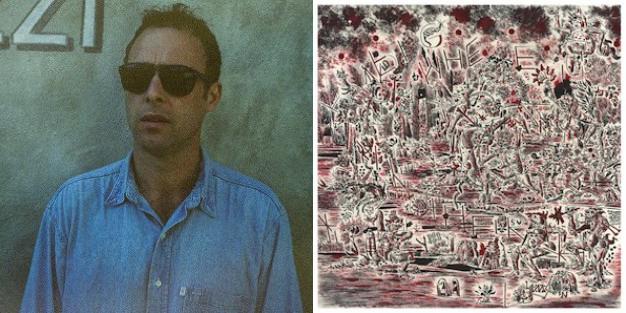

Delicate Steve, aka Steve Marion, is a multi-instrumentalist and songwriter based in LA; Luke Temple is a singer-songwriter and producer also based in LA, who’s fronted the bands Here We Go Magic and Luke Temple and the Cascading Moms, and performs solo as Art Feynman. Steve’s new record, Luke’s Garage, was recorded at Luke’s studio — which is also where they recorded the following conversation. Here, they talk about recording routines, the elusiveness of songwriting, and more.

— Annie Fell, Editor-in-chief, Talkhouse Music

Steve Marion: We’re live… Hello, Luke. What’s going on?

Luke Temple: A little sweaty. Just finished a session at the studio that we’re doing this talk in — that you recorded your album in.

Steve: Which now, is it officially called — ?

Luke: Luke’s Garage.

Steve: Is that right?

Luke: Well, now, because you’ve decided to call your album Luke’s Garage, I’m just gonna use that as the name of the studio.

Steve: I’m happy you like the name, and I’m happy that it’s now the name of the studio. Obviously, if you didn’t like it, that would be…

Luke: I mean, I like it enough that I’ll put it on the record. I made a record here this year and I said in the credits, “Recorded at Luke’s Garage.” I won’t advertise it necessarily as such, only because it feels corny to name my studio, for some reason. I like the idea of it being very casual. And if it becomes like a business or a brand, then that’s what it’ll be. If someone asks for their credits, it’s Luke’s Garage. So thanks for that.

Steve: I made a record in your studio — which I really think you produced, in a way.

Luke: Did I?

Steve: I think so.

Luke: Just by, like, buying the instruments that were here?

Steve: I think just how it all worked out with the space.

Luke: It’s a very Cage-ian production. It’s the fact that I wasn’t here.

Steve: But you very much were…

Luke: [Laughs.] Right.

Steve: Yeah, I don’t know, it was really cool. It gave me a space to really feel like a normal recording studio thing. I don’t know how most bands do it, where you’re on the clock right away and you’re hoping that this is gonna be good, good, good.

Luke: That can yield good results, because you’re not sort of labored with too many options. I’ve been really productive here because, come hell or high water, I’m just going to be productive since I have this space. But I find that having the tools now at my disposal and being able to record drums and having more microphones and whatever, I can get mired in what-ifs.

Steve: Yeah. I think what you just said — “I’m going to be productive just because I have the space” — I feel like that’s what the ethos of my album was. And that’s kind of how you, in a way, produced the record, by giving me the space and making me feel that same thing. Like, I have the space, I’m going to be productive. Because I don’t really write stuff before I go into a studio. It was really, really fun to be in here.

Luke: Did you have a process or was it different from day to day? You were here for two separate months, and you’ve now made three albums here, right?

Steve: Two.

Luke: But didn’t you start a third?

Steve: No. I was here two separate chunks: One just recently, which I think I made a whole ‘nother record. But for the album that’s coming out, it was three weeks in January. The fires happened, like, the second day I was in here. That was pretty gnarly. But after a couple of days it died down, the same thing came back like, I have the space, so I’m going to be productive. What literally else am I going to do today? All the windows have to be closed.

Luke: There are no windows in here, so that’s fortunate. But there is frosted glass doors, ladies and gentlemen. In case anyone would not want to work here because of the lack of light, there’s actually nice diffused light that comes in these frosted doors.

Steve: It really is special. It’s got your vibe in here too.

Luke: Well, that’s nice to hear.

Steve: It sort of doesn’t have to do with the gear at all, but also does. So you have made how many Luke Temple and Luke Temple project records in this space?

Luke: I’ve made one full record. I mean, if I was to not edit myself so intensely, I’ve probably made a couple. But I’ve distilled one down to where I’m happy that’s an album. It’s my other Luke Temple and the Cascading Moms band I have here in LA, and then I’m sort of farming a bunch of ideas that I have floating around for an Art Feynman record, which is another pseudonym that I go by. There’ll be periods of time when I’ll decide to come in here and use only four-track, for instance, and I’ll try to just record something early in the morning. Usually for the Art Feynman stuff, I try to stay away from writing a song, necessarily. I’ll just kind of vibe. And then historically speaking, for Art Feynman, I would then take that sort of raw data and build a song on top of it and produce it. But now I’m trying to just farm that stuff and leave it as is and release maybe an instrumental record, almost ambient. But it’s hard for me to not want to squeegee every last drop out of something. So I’m trying to hear if something captures my interest on just a feeling level, I’m marking it, and I’m just trying to leave it alone. Because I just worked on this Cascading Moms record, where I got into all the minutia of mixing and recording and getting perfect sounds and everything, I am trying to go the opposite direction with this more patchwork ambient stuff, where I’m not even mixing it, I’m just kind of stitching ideas together and letting them be as they lie. And it’s very refreshing because I think sometimes when you start to then, quote-unquote, “produce” something, you suck that original life out of it. Not all the times, but sometimes.

Steve: I was gonna say, how I like to work on music is very much like, I need the confines of a time range. Which is why it’s so helpful to have had your studio for X amount of days. But if you had two weeks where you’re like, “I’m making my record,” and you’ve got that whole time open, what’s the rest of your day look like when you’re not working on the music?

Luke: I have a pretty consistent morning routine, regardless of whether I’m working on music or not, that I try to stick to. Ideally, I wake up early, before 7:00, and I write in the morning three pages. Lately I’ve been writing what I did the day before, just like a series of events from the morning to the evening. And I find that it’s really illuminating.

Steve: I started doing that when I was living right up the street in 2020, writing three pages a day. My friend told me about it.

Luke: The Artist’s Way. Is that what he was referencing?

Steve: Probably.

Luke: I think The Artist’s Way is you just write whatever stream of consciousness, you have no agenda at all. I think the idea is that you’re waking up and you’re in this liminal state from dream into waking, and in that state you just let it fly. I do that from time to time, too. I find that it’s really helpful to do that when I’m experiencing writer’s block. But lately I’ve just been writing the day before, and then I’ll do some exercise. I mean, it’s pretty boring, but it’s structure. For me, having a structured day is of the utmost importance. Because the creative process is so chaotic inherently. You can never plan when that’s gonna dawn upon you, some idea. But what you can do is set your life up to be available for it. So the morning is usually very predictable and routine, and then I’ll come in here.

I’ll come in here pretty early if I have a week where I’m just gonna work on my own stuff. I find that if I start in the studio by 9:00, I can usually go through the day and do an eight hour day. And if I’m really into it, then I’ll overwork and I have to stop myself. Usually I try to do an afternoon walk or something. And now I’m married, so that creates a structure. My wife loves to eat dinner together, so there’s a wind down at the end of the day. But if I don’t get to being creative in the studio early in the morning, it’s hard for me to get to it in the afternoon. If I have a bunch of errands to run and then I come in here midday, I just feel like I’m nodding off.

Steve: When I was recording here last, a couple of weeks ago, my car broke down for a couple of days. The mechanic I go to is half a mile from my house, which is two or three miles from here. So I brought the car to the mechanic and then walked from there to here, which took 45 minutes, which is something I would never have done, and it was awesome. I know that I’m wrong about so many things, and I get in this routine because I like the routine, and then something breaks it and I’m like, Oh, actually, that was what I needed.

It’s really fun making music. It’s just fun to be present in the studio and working on something and feel good. It’s also fun when you don’t, as long as you’re not hitting a pit of despair — which happens to me a lot, but didn’t at all this last month. I’ve never really worked this way. I came in here at, like, 9:00. I would pick up an acoustic guitar, 12-string, or go behind the drum kit and just play to a click track if I had a couple of chords, and I would make sure it was one take. I made all these songs — they’re full songs with chords and stuff — but totally one take.

Luke: Wow.

Steve: And I would think, Well, that guitar was kind of sloppy anyway, so maybe I should do another. But I had enough willpower in the little moment to go, I’m just going to keep that guitar. And I think that’s the whole difference. I had this guitar that gave me a little sort of off feeling, but I would play everything to that, and that would loosen me up on everything else I was doing. And it would just sort of cascade quick enough before I got sick of anything that, by the middle of every day, I had a song. Then I would kind of get hyped and walk around the lake or go have lunch or something, and then come back and I would mix the song by 4:00. And all this batch of 14 songs, I’ve only listened to them in the car on the way home from something, like, two times, and they’re stuck in my head. So this is the first thing I’ve walked away from where it’s incomplete, but they’re fully formed, and they’re all fully formed in one day. I’m feeling really enthusiastic about music from that. So thank you again for producing another album.

Luke: Man, thanks for gracing this space. It makes me think about some quote I heard — someone was quoting Neil Young and he said, “If something I’m doing is making me kind of uncomfortable, I know I’m onto something.” And what you were saying, like if a guitar’s a little sloppy and your knee jerk from recording all these years is to go try to fix it, but then you use that very imperfection as a crux point to springboard the rest of the track — it’s similar to what I’m doing when I’m farming all these random ideas that maybe I did and I was like, Oh, this is garbage. This is just not going anywhere. Where’s the song? Where’s the melody? And then the in-between things that I didn’t take seriously because something about it just made me feel like maybe it wasn’t me in some weird way, but then in hindsight, listening back, all those little interstitial bits are more me than anything.

Steve: That’s, I feel like, the hardest thing to do with self-producing, self-recording — it’s this micro moment where it’s not even so much the guitar makes me feel uncomfortable or that it’s good, but as soon as I start to analyze it and be a producer guy, then I’ve put my producer hat on and I’m not just being a musician. I will go to the producer mode way too soon and I’ll stop myself like, Oh, that guitar — and it’s just you not talking to anybody for eight hours or whatever. It’s wild to think these little moments that you kind of aren’t cognizant of can change everything.

Luke: I don’t know if it’s coincidence, but — and I’ve had a few different projects that I’ve written under — relatively speaking, anything I’ve done that people have liked has always been the stuff I gave the least fucks about.

Steve: Oh, totally.

Luke: By far. The first thing that people seemed to like was the first Here We Go Magic record that I did on cassette tape. I was so tired of going into studios and people telling me what I needed to do and what I didn’t need to do, and I needed to record to a click or whatever, that I recorded it myself. I sort of had to bust through this notion that recording was some dark art that I wasn’t allowed into, and I just realized it’s an ear thing, it’s an emotion thing, and that’s about it. Because I had always recorded ideas on my own to demo stuff and I just decided to go with the demos. But in an act of rebellion at the very end, when I sent the record in to be mastered, I sent the guy MP3s.

Steve: I remember you saying this.

Luke: Because all this talk about like WAV versus EMP — this was in the sort of Napster days — and people were up in arms about the sound quality. But this was kind of a mono record recorded to cassette tape, and I sent the guy MP3s, and no one’s ever said anything about that. I mean, maybe it would have done better if I sent him WAVs. But it just goes to say that I think as long as you have your feeling in there and your intention, that’s really all that matters. If your thing is high fidelity, that’s part of your sound — like a Talk Talk record, for instance, it’s part of that and it’s almost like an effect — then do that. But it can’t negate your feeling. If it means interrupting the flow, I don’t think it’s worth it.

Steve: I mean, that’s just what’s so cool about art. You capture it forever in this thing and it doesn’t have to do with any of the stuff you’re actually using. Unless it does.

Luke: Well, that is part of it in the end. That’s how it comes to the listener: It’s with the sounds outside of the window. It’s with the dog barking. It’s with the hiss. All of that stuff. It doesn’t make it any worse having that stuff there. It’s not like you have to clean it up in order to present your idea perfect, as if our ideas and our songs are sort of a vacuum outside of reality. Anytime you sing a song, it’s in a space with a certain reverb quality in the room and with people coughing. There’s some aspect of the world coming into it always. And I think it’s more interesting to capture some of that, even in the fact that maybe just you don’t know what you’re doing as an engineer and you set up in a weird way. Like, I produce people now, and I have clients that bring demos in to me and I have to kind of bite my tongue because I need the work, or they’ve already booked a week. But I hear the demo and I’m like, Oh, man. I want to just be like, “Go home. I’ll master this. Just release this, because there’s no way to make this better. If you’re going to try to chase this idea, you’ve already done it.”

Steve: Yeah. Essentially I’m just recording demos all the time and I’m trying to polish them. There’s never a second time I play the guitar part or the opening thing where I’m like, OK, now I’m gonna really do it, because it’s just gone.

Luke: At least in terms of singing, there’s never a time where a song conveys the emotion the most as pre-lyric when I’m just singing phonetically.

Steve: Right.

Luke: And then I’m like, something about the way those syllables sound, I’ve got to write words to fit. And it always cuts about 30% of its effectiveness. So no one has ever heard the song the way it really should be. I mean, certain people, like Cocteau Twins — she just sings made up words, I’m assuming because of that aspect, that phenomena.

Steve: Whatever your concept of your song is and your idea, you gotta fight getting that imaginary thing out your mouth or out your hands and then into the technology you have and that’s going to diminish from whatever that thing is in your head that you’re chasing.

Luke: There’s this guy, Rudolf Steiner — I think it’s called Theosophy — he was the leader of this whole metaphysical school of thought, I think in the 19th century. Anyway, he had this belief around building and making art in general that these structures that we create exist anyway and that you’re only bringing them into reality. So almost like a sympathetic frequency of a room, for instance — it’s waiting to ring. When you’re in a venue and there’s maybe some note that when the bass hits or the kick drum and the whole room just goes — and it’s annoying in that context, because you don’t want to have an F sharp going the whole time — but I think that’s kind of what it is, like that room exists in an F sharp. And until the right circumstances create that to express itself, it’s sort of latent.

Steve: That’s like the whole theories of consciousness too. Consciousness is just things waiting to be explored.

Luke: All the information is there. Everything has been created. Nothing is created or destroyed. I think that’s sort of proven — well, to some degree. I mean, in physics, all matter was created at one time and it’s just sort of recycling. I think we can’t measure these subtler frequencies of emotion and thought, but they are part of the universe at large. There’s a physicality to them. There’s combinations, there’s math, there’s structure in them. There’s structure in an emotion and there’s structure in a thought, in a visualization. And I think that we become sort of a conduit to express something like a design that is wanting to be expressed. And I don’t even necessarily think that’s very woo — I feel like it’s just a subtler science that we don’t have any way of measuring.

So to what you were saying, what we were both saying, about an idea existing in your head in its purest form — I mean, it’s always going to be diluted. That’s the irony of it. It exists in potential in its purest state, and the second you manifest it in reality, it is one foot away from heaven.

Steve: There’s that side of an idea where you’re like, Oh, my god, I just wrote “God Only Knows” but I only have a PreSonus mic preamp or whatever — that hardly ever happens. For me, it’s more the opposite where I’m like, “I got this thing that’s half fine,” and then you collaborate with somebody and the output of that is like, Oh, my god. That’s another wild aspect: somebody else comes along and just might just make sure you don’t get in your own way by saying, “I like this. Don’t do that.”

Luke: Mutts are healthier dogs; genes expressing themselves in more variable ways is a stronger gene pool. I think it’s probably the same creatively speaking.

Steve: Sure. I don’t know what we say… Thanks for reading.

Luke: Alright, well, nice talking to you, Steve.

Steve: Nice talking to you. ‘Til next time.