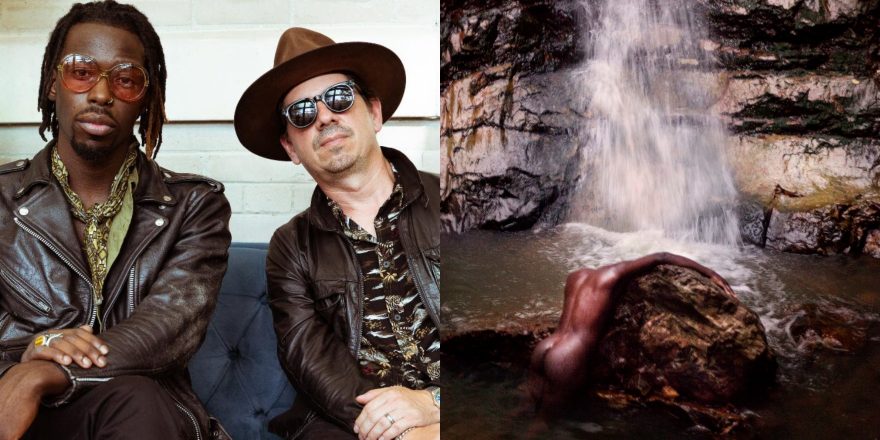

Mocky is a performer, producer, songwriter, composer, and multi-instrumentalist based in LA, who’s worked with the likes of Moses Sumney, Feist, Kelela, and many more; Jack Stratton is a multi-instrumentalist, and the founder and leader of the band Vulfpeck. Mocky’s latest record, Music Will Explain (Choir Music Vol. 1), came out last month, and to celebrate the release, he and Jack sat down to catch up about the science of the backbeat, capturing the sound of humanity, and more.

— Annie Fell, Editor-in-chief, Talkhouse Music

Mocky: This album is all about space — physical, emotional, sonic.

Jack Stratton: When I moved to LA and met [you] through Joey Dosik, I didn’t really know you, but you’d usually launch into some philosophical rant on the grid, or the atomic nudge unit, and were somewhat dogmatic about not using clicks.

Mocky: So, for your average person reading this, none of that makes any sense, so let’s see if we can break it down. The click is the modern way of recording to a metronome whereby the computer sets the heartbeat of the song, before you maybe even wrote a song.

Jack: Right. And if you’re like me, coming out of a love of studio drumming, it progressed into being able to play with a click at a certain point, maybe in the ‘70s or ‘80s. But you rejected all that, and it was freeing for me at the time. If you just go along with the herd, you’ll be playing to a click… But then you flipped it again years later.

Mocky: Well, sometimes you use a click. It’s all relative. But I think what’s important is every backbeat has to have its own life, its own intention. Every single backbeat is the opportunity to state how you see the universe. So to just sit back and try to be as good as a machine — I can’t get into that. The song dictates the backbeat. That’s the interplay. In the ideal situation, the melody and how it interplays over the backbeat is what it all boils down to.

Jack: So what was your progression to that rejection of certain things? Had you done that in the past?

Mocky: It was coming out of doing a lot of electronic music in Berlin, where it was all machinic. But to make something truly modern, I needed to create my own samples. I had to create a musical moment in time that went beyond just this kind of loop.

Jack: Right.

Mocky: And that brings us to this whole idea of space. It’s a certain sense of dynamics that you can only get when you see through time in the whole three minutes and 40 seconds, then you understand where the peaks and valleys are and where the loud hits are, the quiet hits, and where the melody goes up and down.

Jack: Right. So whose backbeat, producer or drummer, are you most influenced by?

Mocky: I mean, you kind of have to say Stevie [Wonder].

Jack: That’s crazy.

Mocky: Because the song always carries it, and the backbeat reacts. I’ve never had such a consistent, robotic sense of time anyways. It’s always a little off, but that’s what makes sense to me.

Jack: I got to ask Bernard Purdie who had the best shuffle and he said Panama Francis, who was a session guy before him. “The Wanderer,” and then a lot of Frankie Valli…

Mocky: That’s what he did?

Jack: Yeah. You heard it here first. But, yeah, Purdie’s backbeat is probably mine. Or Maurice White.

Mocky: And nobody owns the backbeat. That’s the crazy thing about it — it’s like a wild animal, it all depends on what’s happening in the moment. That’s the whole point. Anybody can make the dopest backbeat. Like, a toddler can be delivering the dopest backbeat.

Jack: I’ve seen that, yeah.

Mocky: That’s what we’re talking about. It’s almost like the space before the backbeat is much more important than the backbeat itself. That’s something that I often think about when I’m laying down tracks and working with people. You have to be willing to just let it hang for one second and then hit it a little ahead of time. It’s a weird combination of dream peddling in the moment, so you’re sort of never late, never early, but right on time. But not relative to a machine — right on time relative to exactly whatever everybody did the second before that backbeat. And then that bar later, same stakes. But I think what’s interesting is the idea of space, by using the tape machine, that sort of enabled me to use more highs where the symbols and the snares are. And the hi-hats normally sound annoying on the computer and you can’t really boost them, so in that high register, you can find new sonic space that then houses the emotional space that we got with the choir singing in unison. It’s the idea that you have this one mic with multiple voices singing in unison, so before they hit the mic, they blend so they sound like one voice. So there’s no way that AI can get in and unpack those voices. Whereas most music made today can be taken apart by AI, I managed to Mock-enheimer a sonic thing in my garage whereby I actually can’t get in between these people.

Jack: It’s encrypted.

Mocky: It’s encrypted through just the singular mic and unison. No harmony. When I started, I was doing all these intense harmonies, and I realized quick that it was more powerful to just have everybody do a unison part, and thereby blend their voices into one, then to one mic, and then straight to the tape machine. All before going to any kind of computer. So it becomes a sound that’s, like, superhuman, by today’s standards.

Jack: Yeah. It was a strange process connecting all the Mocky stuff, because it’s with multiple artists and then there is the Mocky solo releases. But there is the thread of this backbeat and the way you could still tell it’s Mocky, but you would layer this cascading backbeat.

Mocky: The flange.

Jack: How did you develop that, and how do you do it? It’s like a magic trick.

Mocky: Each instrument, I kind of play a different persona. So if I’m adding, say, the tambourine after the snare, I have to kind of imagine that person and how he walks through life and why he would hit it a little bit behind. So I invest it with intention. And what year is it? It’s often 1974, which was a great year for music… But playing these characters as you build the track, it gives you an excuse to make a mistake. It’s not about being right. It’s about being wrong, but still getting away with it.

Jack: Yes.

Mocky: Then the thing has a bit of life to it… The album is called Music Will Explain, and it seems to be true.

Jack: It’s a great title. Care to explain?

Mocky: I mean, a lot of musicians talk about how their music is therapeutic or whatever, but I think for everybody, music has a role to play in their life. And the emotions and the kind of requisite empathy that music calls of on a human are big seeds in the operation of growing understanding about life and yourself and what you’re going through. So in my case, through writing songs, I find that I make sense of all the craziness and the chaos and the volatility and the beauty — just like it says in the song. But it’s a deeper sentiment in the sense that for everybody, you can find answers in music. Because music in its nature is about connection, human connection, which I think ultimately is needed more and more with every passing hour. There’s dog hours, and AI hours are even faster. They’re putting it on us, this sense of having to rush to keep up with with the tech.

Jack: Yeah. I remember early Wikipedia, the feeling of, Oh, wow, I can get up to speed on something so much faster now. And now that just got 10 times faster. The speed is insane, and it’s exponential.

Mocky: Yeah. That’s where music comes in to answer again: Music is the thing where you can stop time, you can change people’s perception of time. J Dilla. You know what I mean? There’s somehow this extra time in between the beats that doesn’t make any sense. He’s built a time machine. And so did Little Richard, because Little Richard was doing the same thing — just kind of playing straight, 4/3. 4/3 is the ultimate clave. That’s what all distortion pedals basically mimic. And Little Richard was sort of creating distortion by playing straight while everybody else was swinging right. So from Little Richard straight through to Dilla, and everybody in between, there’s this sense of when you’re really swinging, when you’re really rocking, when you somehow got around time and made something that bangs — that’s what we’re talking about. It’s sort of a version of time travel.

Jack: Yeah. I’ve been on the rabbit hole of train funk, the mechanized funk of a steam engine.

Mocky: The post-industrial roll of the train as it relates to the backbeat. [Laughs.]

Jack: Oh, definitely. I mean, Purdie said his biggest influence was the train. And I think there’s an emotional component to it — it feels like you’re moving. And then something about the train engine, where it’s human and mechanical — a perfectly synthesized beat is not that interesting.

Mocky: Yeah. At some point, to make the most modern electronic music I could, I had to be able to make the most high fidelity acoustic sound I could. That’s the whole nature of electronic music anyways. I mean, I put it all in ProTools in the end and do things with it. But it’s about what you’re capturing — what spirit you’re capturing and what kind of fidelity you’re capturing, what space you’re creating.

I think the thing is, we can talk about backbeat and funk all day, and people are gonna read that and think, OK, this is just the usual funk shit. But it’s not, because the truth is, backbeats themselves are meaningless if they’re not backing something up. A backbeat is nothing, actually.

Jack: Well, that’s true.

Mocky: It’s reactive, but it’s gotta back something up. And I think that’s where it comes down to being a one-of-a-kind and not following trends. And ‘peck never followed a trend. ‘peck set trends.

Jack: [Laughs.]

Mocky: [Laughs.] And it’s the same with me. I probably couldn’t follow a trend even if I tried. Lord knows I probably have tried. At the end of the day, you gotta find your own voice, whether that’s note by note, chord by chord, project by project, project name by project name — you gotta be an original and stand and walk and fail and succeed in that truth. And if you do that, you might have something to say. You might actually have something to say through learning a thing or two or two, and having a life that then translates to music. And then you have something to put the backbeat on.

Jack: Yeah. It’s a humbling journey with the backbeat.

Mocky: Song versus beat is such an interesting equation. Because sometimes the beat is driving and the song is in the passenger seat. Or other times, the song is in the driver’s seat and the beat is in the passenger seat. It’s sort of one or other. And when you keep zooming in, there’s this rare finite space where you get both. But a lot of times, it’s like a funk banger that you’re not gonna really be able to play by the campfire. Or it’s the opposite, where it’s a beautiful song that was written and the challenge is to keep the tempo up or to put it over a fat beat or the right find the right drummer.

Jack: Yeah, yeah.

Mocky: And then you have these certain songs that get both. That’s the sweet spot. I think the ‘80s really nailed that, with the Linn drum, the LM-1, coming in and raising the bar. With still the musicianship around it — aka, Prince. Aka, every single ‘80s musician suddenly playing along with LM-1.

Jack: Wait, I got something: You’re trying to do the same thing Steve Gadd did in a totally different way, where he somehow made it through the click era and can play to click, but you don’t care that [he’s playing] to click. He somehow makes that work, and it doesn’t sound like he’s playing to click. And you’re in this situation where the technology’s gotten insane and you—

Mocky: Are free-floating.

Jack: It’s not playing to click, but playing to technology, where it’s like everyone can know what you do but they don’t know how or why. I can think of the sound of a Mocky track. It’s definitely not the mixing.

Mocky: Well, it’s a big part of it. Renaud Letang, and everybody who’s mixed with me. Zé [Nando Pimenta] in Portugal. But I think more and more, it’s like pushing through time. So in the case of Music Will Explain, that’s using the human voice primarily way up front with no chance to fix it and just waiting until that moment of magic happened — which sounds like the most obvious traditional thing. Isn’t that what they did? Yes, but they didn’t have ProTools at the same time firing on all cylinders, making this kind of sculpture in space and time, and then using all the old vintage gear to back up a modern song. The song “Today Years Old,” which is built off a meme, is sort of touching on this. So ultimately, the goal, the reason why, is to capture the sound of humans in a modern sense, in a modern time. Not to be cut out from it. And it’s been that. But the most interesting things were always when a human was making something backfire because they didn’t really know how to use it right.

Jack: Yeah. Usually you get that from two people collaborating, some lunatic who hasn’t touched their studio and then some modern… But you’re trying to do both, which has gotta be schizophrenic at times.

Mocky: Maybe that’s why I have a choir singing — one for every personality. [Laughs.]

Jack: [Laughs.] It’s a fun practice, though.

Mocky: Yeah. And it’s a soul-seeking practice, trying to create an album. Which most people would think, “Well, why are you even trying to create an album anymore?” But for me, it’s another way to create this three-dimensional sort of sculpture that can then hold space and time — to make the Mock-enheimer time machine, basically.

Jack: You’re trying to, like you said, embody or mimic the sound of people playing at once. That’s hard.

Mocky: That is hard. Also, just hearing something that you like from the old days and then trying to recreate it and take it into the modern world with an actual experience — whether it’s writing or producing, when you’re with people doing something and you share a moment, that’s the easiest thing to translate into song. Whether it’s, “Oh, that’d be a funny lyric,” or it’s a moment where everybody’s laughing that you leave on the tape, or group hand claps. Capturing that magic, that humanity, in these times of AI, couldn’t be more important.