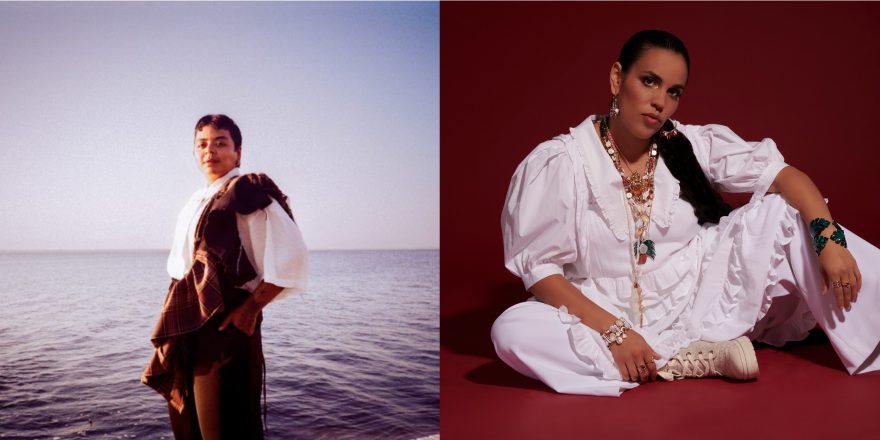

Émilie Quinquis, aka QUINQUIS, is a Brittany-based musician who sings in the Breton language; Gwenno Saunders, aka Gwenno, is a Cardiff-based musician who sings in her native Welsh and Cornish. In honor of their respective records — QUINQUIS’s eor was just released last month, and Gwenno’s Utopia (her first record in English) will be out July 11 — the two got on the phone to talk about preserving their cultural identities through their art, and much more.

— Annie Fell, Editor-in-chief, Talkhouse Music

Gwenno: Hi, Émilie.

QUINQUIS: Hi, Gwenno!

Gwenno: It’s so nice to finally meet you. I haven’t heard your record yet, but I’m really excited to hear it. Is it in Breton again?

QUINQUIS: Yes, it’s mainly in Breton, but it’s also in Zulu and Welsh.

Gwenno: Oh, wow! Who’s singing in Welsh with you?

QUINQUIS: Cerys Hafana.

Gwenno: I love her. She’s fantastic. And is she playing the harp for you as well?

QUINQUIS: Yes. It was a nice experience, a very smooth the way of working, and the result is really great, so I was very happy. And in Zulu I am working with Desire Marea, who is a South African artist. We never met, but I’d seen them in Berlin just after COVID, and it was such an experience, the explosion of joy during that gig. So I really wanted to work with them and I’d been thinking about them during the whole recording process. For every track I was thinking, OK, maybe this one could be the one I could send to them. We were working long distance with Cerys, Desire, and also Gareth Jones who wrote the record with me. I’ve read that you recorded your album live in the same room.

Gwenno: Yeah. Rhys [Edwards] and I had been working on the songs as a duo in the studio and trying to work it out electronically, but it just felt like we weren’t getting the energy into the songs. I was like, “You know what? We’ve got a band, we play live — why aren’t we in the room together and feeling what that is?” Because I think particularly in the world at the moment, we’re so isolated from each other, and I really wanted to feel the reaction from each other musically, because it was something that I hadn’t done in a really, really long time.

I gave them the songs a couple of days before, and then we just went in. We didn’t do it to click — which was a bit of a mistake because it cost us a few months of editing. But I was so in the moment going, “Oh, this feels good, let’s just record it. This is just pure human emotion.” I would love to make that record where it’s just us in the room, but there was a lot of editing post-recording that was unavoidable. I would love to avoid that in the future, because I’ve never made that kind of album.

QUINQUIS: I find it very organic, the result on your album. You can feel the room and you can feel there is no click. Do you consider it a political statement to work like this?

Gwenno: Yeah, I think so. I think as an artist, if you’re exploring anything at all, there’s an element of political expression in that, whether it’s obvious or not. And I think especially, obviously, with minoritized languages as well; I’ve had a lot of different experiences in different languages, and that’s what I was trying to explore with this album. I was conscious that I’d had a lot of English language experiences, relationships with people and quite important moments in my life that had been in the English language, and I wanted to acknowledge that. I felt that by not embracing the English language at all — and I needed to do that, I needed ten years off to just not use it at all — it was nice to come back to it with fresh ideas and to put it in the context of the other languages as well.

I always felt that I wanted Cornish and Welsh to be as prominent in my life and in my work as English, because that’s how it is; those languages all sit together, and you have different things to say in different languages. Do you sing in English at all now, or you’re just singing in Breton?

QUINQUIS: I have one track I’ve sung in English, and it was a very different approach for me. I began singing in English at the very beginning [of my career], but I found a way of melody that was really linked to Breton culture and language. I began exploring a different way of singing when I began doing that, and now that I’ve done it, my way of singing in English has changed too. So, I’ve got two questions: What is the first language you ever heard as a baby? And do you think that your way of singing in Cornish or Welsh changed your way of singing in English? Or the opposite — your way of singing in English changed your way of singing in Cornish and Welsh?

Gwenno: Without a doubt, I think that my singing, particularly in Cornish, has influenced how I sing in English and how I phrase things. I think it’s helped me find my voice as well. Because that was the other thing — before I went back and sang in my home languages, I was not sure how I was supposed to sing or who I was supposed to be. And I think going back to my root languages and my childhood really helped me establish who I was most natural being. You can be whoever you want in music and you can try things on, but I think it helps to have at least an inkling and to understand your voice better in whichever language is your first language. It’s definitely influencing the way I sing in English now.

The first languages — I would have probably heard Welsh and Cornish equally at home, and the Cornish would have been quite a prominent language in the house because everyone spoke Cornish to my dad, although I speak Welsh to my sister. But I’m from Cardiff and the English language is far more prominent here than Welsh, so English has always been really a big part of my day-to-day life as well. How about you? Your were you raised in a Breton household, a Breton speaking area?

QUINQUIS: No, there are very, very few [Breton speakers], at least from my generation. And now some people are trying to raise their kids with the Breton language. I’m raising my my son in the Breton language.

Gwenno: How’s it going?

QUINQUIS: It’s going well. But my mother stopped speaking Breton when she was six because of the French government’s issues with Breton language. In school, it was forbidden to speak in Breton, so she decided not to speak in Breton to me when I was born. So my very first language is French. And I’ve decided to relearn Breton, because I could tell that it was missing in my construction. It’s not my mother tongue, which means that sometimes it can be very hard for me to write in Breton. So it’s a kind of everyday work for me to keep going in Breton.

There is only one track in Welsh on your album, right?

Gwenno: Two.

QUINQUIS: Two, OK. And so are you feeling a social pressure because you went to English?

Gwenno: I think you have to explore as an artist. I think you have to not repeat yourself. And I think you have to explore your whole being and you can’t restrict yourself from any part of who you are. I’m quite autobiographical musically in my songwriting, and it just felt like, because I was raised as a Cornish and Welsh speaker — and Cornish has, like, 500 fluent speakers. The Bible wasn’t translated to the Cornish language; a lot of people were murdered in an uprising to try and get the prayer book in the Cornish language. So Cornish hasn’t had that structure in very important periods in history. I don’t speak any other languages. I’ve been given these languages, and I’m very grateful for them, but I use them as tools. And I think as an artist, it’s really important to focus on creativity rather than responsibility. When you’re being creative, I think you have a responsibility — of course you do — but it’s not the thing that you can be thinking about when you’re creating, because you have to create out of curiosity. You can’t create thinking, Oh, what would that person think? How would that person feel? I think that sharing your whole self honestly is all you’ve got.

So I went back to Cornwall and I was like, I can’t make the same album again. And then I started thinking about all the other places that I’d lived and I’d cared about and the people that I knew, and I was like, I just want to create a document of that. Being a mum to two young children, being the age that I am, you know that your younger years are behind you and you’re going into this new period, so I wanted to consolidate and acknowledge everything that happened. I was in an English indie pop band when I was in my 20s, and I’ve never wanted to deny that that happened. I think life is really messy. The way that all the languages fit with each other for me, it’s a jumble. It’s just a mess of life. It’s like a really overgrown garden, and I’m not trying to put an order on it. And I think that if I was to say, “I only sing in Welsh and Cornish,” it wouldn’t be fully honest about what I am, because I’ve had this massive life in the English language as well. I’m working out what the relationship is between every language, and I think the fact that I’ve ignored the English language for a decade has allowed me to approach it again with sort of a respect that I perhaps didn’t have.

Also, it can get quite lonely [singing in a minority language] sometimes. And I was just like, Oh, gosh, how would it feel if I sang and people understood me? That’s a novelty for me at this point. Especially when you’re trying to be as intimate and honest as you possibly can about something, it’s like, How would that feel? Do you think you’ll sing in English again?

QUINQUIS: Yes, I think I would. But I found that way of hiding behind words — hiding behind that mysterious language — was kind of convenient.

Gwenno: Yes! That’s exactly how I felt. And I think for me, so much of exploring Welsh and particularly the Cornish language has been me hiding away from the world, because it’s a really vicious, horrible place, and wanting to retreat into my childhood, into the comfort of that, through the language. I take a long time to process things, and I think my first three albums really were about my childhood in an abstract way. And now I’m sort of going into my teens and 20s…

I think my parents really dominate my artistic life in a way, because they’re the ones that have given me these languages. And, you know, the most rebellious thing I’ve always done is turned towards Anglo-American culture, because I know it annoys them. It’s really childish. But I think this time, I was wanting to acknowledge that I did live in North America when I was 17, and that’s kind of where it started. That was me living my own life, making my own decisions. It’s sort of trying to get out the front door of the flat that I grew up in south Cardiff and trying to live my own life creatively. It’s like, every interview or review that has ever been written about my records mentioned my parents, and it’s like, “You know, I made the records!” It’s working out where your autonomy is. I feel like this record’s a breakaway for me to come back and claim it more and actually be a woman in it rather than a child.

QUINQUIS: In your album bio, you were talking about becoming from someone’s daughter to someone’s wife and then someone’s mother, and what it was for you to be a woman. What is being a woman?

Gwenno: I think as a mum, it’s carving out your space. I think motherhood takes over everything, physically, mentally And I had just reached that point where I was like, I’m not going to have any more children, and I want to remember everyone I’ve been, because maybe some of those people I’d forgotten about. And you do, I think, once you become a mum, forget all those idiots you’ve been. And I just wanted to acknowledge those idiots. Because they’re a laugh as well — they were quite good fun. It’s, again, just that whole picture of who you are as an artist. When you’ve got young children, the sliver of time you have for yourself to make the album is so, so tiny. I’m hoping that’ll grow now as the children get older.

How have you felt organizing yourself as a mum and writing and recording? Because you were talking about doing a lot of long distance recording. How are you managing that? Creatively, where do you find the space? I go away for a week and I write an album, because I need that time alone. Do you find that, or can you work around family life?

QUINQUIS: I can’t really do that, so I spend most of my nights taking the time for myself. So I don’t sleep much. I try working during the night so that I can have brain space to really take the time. But I feel a difference between the first things I’ve recorded and the album that is about to be released. All the amount of time you spend in the research mode with gear, and you don’t care if you are going to spend three hours on that loop to make it sound as you would like it to sound — these kind of things, I don’t have the time to do them. But in a way, it’s put a frame on my work that has been very good for me to finish stuff. Because sometimes when the frame is so strong, you find a way to be more efficient. You go straight to the point. I think it’s been kind of a blessing on this album. But right now, preparing for the live gigs, I would like to have a bit more time to relax. It takes organization to find that time.

I think sometimes it has helped me to be on my own working on my stuff, because then I could do it whenever I was available. But sometimes it has also taken me some time off because it was me and myself and and no one from outside telling me, “Hey, I’m here for three days only and we need to work now.” And if my my son was sick, I would stop everything to take care of him, whereas if you’ve got someone here for three days to work with you, you find a solution; you work with your son on your knees, but you still work. I have trouble having as much discipline with myself as I would have with other people around me.

Gwenno: That is interesting, isn’t it? Because you have that advantage of, you only have yourself to explore. But it’s working out the balance as well, because I really like being around other people. It’s hard, I think, when you’re a solo artist, because you want to share it and be like, “Where are we going next? Come on!” It’s that camaraderie. Were you in bands when you were younger?

QUINQUIS: No, never

Gwenno: Amazing. So you just knew, “I’m on my path and I’m really happy here.” I really admire that.

QUINQUIS: You were mentioning the fact that your previous albums are more on childhood and this one is more on your teenage years. It’s called Utopia, which is a nightclub you used to go to. It’s funny because the obvious thing would have been to go into electronic again, and techno, but it’s kind of like you’ve chosen the opposite.

Gwenno: Yeah, totally. I’ve been thinking about that nightclub for a long time. It’s a techno nightclub we used to go to, because I lived in Las Vegas when I was a teenager. Maybe one day I’ll write a piece of music about Utopia and it’ll actually sound like Utopia and what it was like. But I just felt like the words were really important on this record. I wasn’t trying to create a reenactment of the place. It was more about the whole time, and Utopia sort of was a metaphor for the whole period. And I liked that “utopia” means “non-place” originally in Greek, because that’s what Las Vegas is — a non-place. A nightclub is a non-place if it doesn’t exist anymore.

My first job was as an Irish dancer, because I had Irish danced since I was little. It was in Lords of the Dance, and I got sent to Las Vegas. I liked the idea of, my parents had worked so hard to focus on Celtic cultures, and then my first job was in the tackiest place on earth. I don’t want to deny that, and I think actually embracing it is a good idea because you get a bit more of a hold on what it is, and what our relationship is between our culture and that ginormous capitalist culture as well. With the way the world has been going, I think it’s easy to retreat into the landscape and be like, “I reject all of this and I’m going to be this running-through-the-hills sort of artist that ignores all of that.” But I felt like I was wanting to go back into the world and try and understand it a bit better, only from personal experience. I haven’t picked Las Vegas out of nothing. I had experiences there, and I thought that must be able to tell me something about North America — which I was interested in trying to explore at this point because of everything that’s going on in the world.

Do you feel very committed now [to singing in Breton]? Do you feel like the language is going to be something that you want to keep exploring?

QUINQUIS: I feel that responsibility to keep going, because it’s a very endangered language. Also, I think about my son and the kids his age that would need to have some music in Breton. So I feel that responsibility. But I also feel I could totally record tracks in Spanish or in English. The only thing I would feel a bit uncomfortable with, to be honest, would be to write in French.

Gwenno: Interesting. Because it’s that relationship, isn’t it? It’s the brutality of that. It’s difficult. My family has roots in England as well, so I’m not, like, from Wales and everyone’s always been from Wales. My family are from all over Britain. For you, your family are Breton and it’s always been that, I’m presuming. Is that right?

QUINQUIS: Yes, yes. I don’t think I’m committing to only singing in Breton in my life, but it’s helped me so much to express myself that I kind of owe Breton a bit of respect. So I keep that in mind.

Gwenno: I think it’s so fascinating talking to you, because it’s always a fine balance. I’ve got a Cornish song on the album; I’m always going to sing in Welsh and Cornish. But I think that I made a record to just have a bit of space to try and re-approach. Because it’s about working out different ways of exploring the languages that you have and your relationship to them. And I think when you speak a minoritized or an endangered language, you’re far more conscious of what language is. You’re more conscious of how fragile it is.

QUINQUIS: You had this quote from Agnès Varda that says, “When you open people, you can find landscapes.” And that would be my last question for you: If we would open you, which landscape would it be?

Gwenno: I think it would just be the sea. I’ve made a record about cities because those cities are part of who I am, but I think that probably in the end, inside I’m the sea.

QUINQUIS: Maybe it’s just because it’s what links Wales to North America.

Gwenno: That’s true! How about you? What would you be?

QUINQUIS: I think I would be a wood. With all the smells, very huge old trees…

Gwenno: That’s beautiful. Émilie, it’s been so nice talking to you. I feel like I’m getting such an insight into your approach.

QUINQUIS: Yeah, likewise. It’s been a real pleasure.