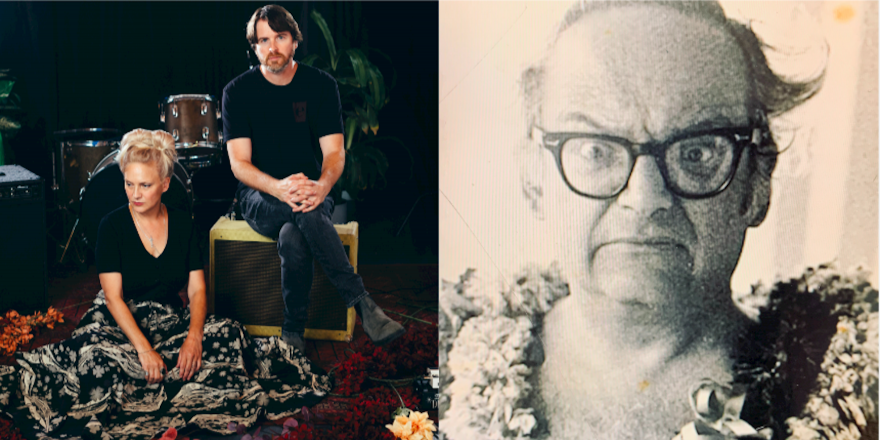

My band was formed as a backing band for master Senegalese percussionist Modou “Mamadou” Mbengue Sarr. A chance meeting quickly became an intense and beautiful musical partnership that changed my life and continues to influence and guide me, despite its tragically premature end.

I first met Mamadou in 2021 when he was on tour and staying with my roommate, Eric Burns. Almost immediately after meeting, I invited him to come down the hall and play some music with me. Though I wouldn’t presume to do this with most musicians I had just met, he was incredibly friendly, and I saw he had his Tamas (talking drums) ready. We improvised for 20 minutes or so, just Tama and drum set. It was joyful and effortless from the first few notes. It was one of those moments that musicians dream of, but are few and far between: Wordless understanding and natural flow.

I left that meeting excited and energized. A few days later, we reconnected and he recorded Tama on my song “In Time,” which was released with my EP the following year. That recording session, which took place in my bedroom, was also full of spontaneity, laughter, and joy.

Originally from Senegal, Mamadou was living in North Carolina at the time, and his stay with us in New York was short. But when he made the move to the city the following year, he asked me to put together a band for him, as his current band members were often on tour with another project. The band I put together was made up of my long-time friends Dan Pierson (keyboards), Dan Stein (bass), and Alex Cummings (saxophone and flute). I had been playing music with all of these musicians for over 10 years in different projects — some close to 20.

From the first time we all got together, everyone loved and respected Mamadou. His joy was infectious and his skill undeniable. Everyone I called for the project is, like me, very interested in learning different styles of music. After hearing my excitement, they were all excited, too, at the chance to learn from and perform with him. The musicians I chose are all versatile, but definitely more jazz-leaning than the musicians in Mamadou’s other band; instead of trying to push us more in the direction of straightforward afrobeat, Mamadou was excited about the change of pace and really leaned into it. He wanted us to open up the music, interact and experiment with different grooves and sounds. He had no trouble conducting it and fitting right in. It really amazed all of us how naturally he could do this. I later learned that, though he came from a background of traditional West African music (his older brother Mbaye and his sister’s husband, Massamba Diop, are both renowned Tama players), he had been living in the US for quite a while when I met him and already had a long history of collaborating with musicians here and leading bands.

Mamadou first moved to Greensborough, North Carolina in 2009 after finishing a US tour with the popular Senegalese musician Abdou Guité Seck. (You can see Mamadou with Abdou Gité Seck in this video; he’s wearing the hat and the light blue and playing two tamas.) Mamadou had family in North Carolina, and decided to stay there. In 2013, he moved to Chicago, where he stayed until pandemic hit in 2020, and then moved back to North Carolina. It turned out that Mamadou and I had been living in Chicago at the same time — I was there from 2013 to 2016, when I moved to NYC — but never crossed paths.

But back to 2022: Mamadou taught us his music by ear, sharing demos and singing the parts. I spent a lot of time with him, learning some of his intricate drum breaks and even starting to learn to play tama. He always brought humor and energy to rehearsals. He was spontaneous. He would start singing or rapping in the middle of songs, and none of us knew what he was saying — it was in Wolof — but it sounded great. He would dance, play his tama behind his back, sometimes two tamas at once, one under each shoulder. We also began to play some of my own music and he was very encouraging. He seemed excited to play it, and wanted to include it in the sets. It was a very freeing and inspiring time for me, having such a great musician that I looked up to support my work — especially songs such as “Peace Groove,” “In Time,” and “Early Waves,” which are based on African or Afro-Brazilian rhythms. Him being a master Senegalese percussionist and encouraging me to play the way I was playing took away the doubt over whether I should be writing in these styles. For better or for worse, I felt like I needed some kind of permission, and I had gotten it.

Like me, Mamadou was truly hungry to learn more about music and experiment. Now, looking back through our old WhatsApp threads, I am reminded of how we were constantly sending ideas back and forth. I would send him rehearsal recordings or videos of me playing through new songs of mine on piano. He would often send me recordings of himself playing tama or singing over the rehearsal recordings. I was very confused as to how he did this until I learned that he had two phones — he would play the voice memo from one phone and record a new voice memo with the other. I thought that was genius. I felt that we were very aligned in our goals, and saw the possibilities of where our music could go if we kept working and growing together, both artistically and business-wise. A breakthrough felt inevitable.

When time came to plan my EP release show in early 2023, it was a no-brainer for me to use this same band, including Mamadou. We started rehearsing and the music took shape quickly and naturally. I was very optimistic for the future. But as the excitement was building, just weeks before the release show, Mamadou tragically and unexpectedly passed away.

The day that I learned of Mamadou’s death was also the day that I met another talking drummer, Baba Moussa Traoré. I was to meet him for a rehearsal for another band, and I almost cancelled it in my grief; I did not want to meet another talking drummer at that moment. But as fate had it, we got along very well, and a week or so later I asked him to play at the release show. Baba Moussa had also known Mamadou and, along with being a great drummer in his own right, helped carry his spirit that night. The show went on, and though bittersweet, it went very well.

I have continued to perform my original music using the same core group that had backed Mamadou, plus Baba Moussa Traoré on Malian talking drums, Rich Stein on percussion, Timothy Bennett on alto saxophone, and Eric Burns — my roommate who had introduced me to Mamadou in the first place — on electric guitar. This eight-piece ensemble has become my band.

Not only do the spirit, energy, humor, and rhythms of Mamadou live on in the DNA of my band, but in my music as well. Because of his encouragement of my sound, I have resolved to unabashedly compose from my influences and what I love. When I find a rhythm or a type of music that truly speaks to me, I like to find my own way of playing it or composing around it. A recent example of this is Chicago Footwork music — especially the music of DJ Rashad, RP Boo, Traxman, and DJ Manny — though it may not be easily apparent in this album. The drum beat for “Pressure” was heavily influenced by footwork music (though it is more obvious on the demo, for which I programmed the drums and is locked at 160 bpm).

Early Waves presents the band at a time when it has settled in its current form. Though I miss Mamadou very much, I have moved forward and our sound has evolved. Still, this band would not have been the same without its origins as Mamadou’s band. Starting off playing mostly groove-heavy afrobeat and learning together with the excitement of doing something new left all of us with a different frame of reference. Mamadou was such a loving, energetic, passionate, and genuine person. I intend to carry his memory with me and in all of my musical projects for the rest of my life.